"The Secret Lives of Playlists"

by Liz Pelly, June 2017

Originally published by CASH Music's Watt

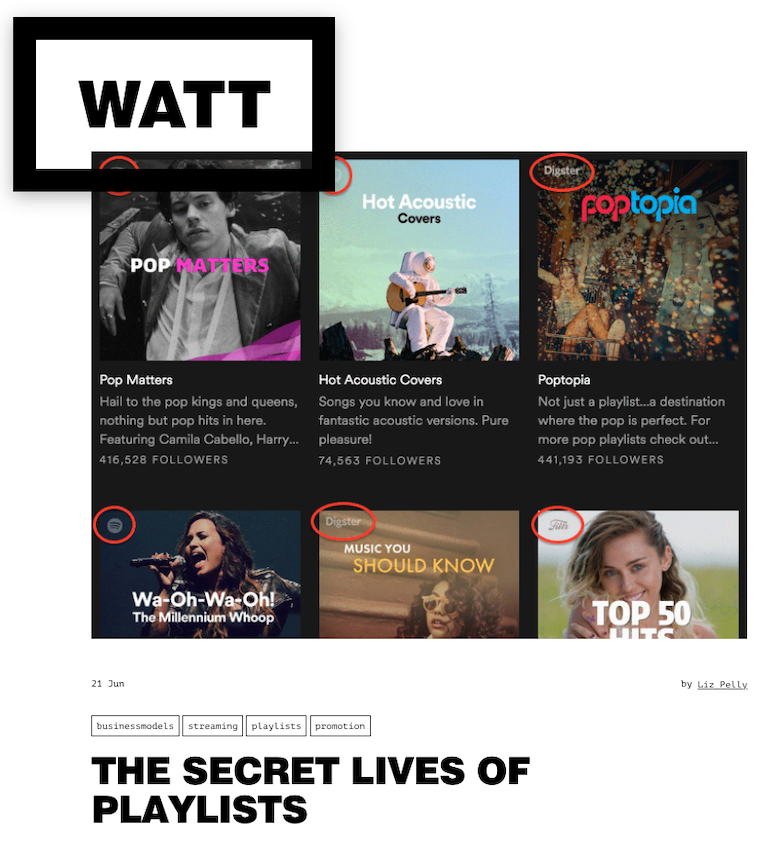

Not all Spotify playlists are created equally. To begin understanding this, look at them closely. Literally. Choose a playlist in Browse, and look at its cover art. Look in the corner for a logo. Look at another. Look at all of them.The vast majority of their square, tinted, Instagram-like front covers will wear a tiny Spotify insignia, that little circle with slanted waves—the artist who designed the logo says it is a visualization of streaming. On other playlists, you’ll occasionally notice different logos: the thick cursive word Filtr, the all-caps logo for Topsify, or simple rounded text reading Digster. These are the playlisting brands owned by the major labels: Filtr by Sony, Topsify by Warner, and Digster by Universal. Very rarely you might see an independent label or brand logo.

That majors own their own playlisting companies servicing Spotify, and that these major-owned playlists have prominent placement within the platform, should come as no major surprise: Spotify is largely a collaboration with all three major labels. But for me personally, as I itched to learn more about industry insider backdoors to Spotify playlists, learning about Filtr, Digster, and Topsify was illuminating; the beginning of my journey attempting to unpack this mystified world. As it turns out, these privately owned brands barely scratch the surface of what’s at play.

What are we looking at when we open Spotify? How did it get there, and on whose dime? Who owns visual real estate on Spotify? How do major labels control what the average Spotify listener is being fed? Who is shaping Spotify’s so-called “editorial voice”? Why is it so hard to tell which playlists are curated by humans and which are curated by algorithms? And how is the latter increasingly shaping the former?

Spotify is currently striving for a never-before-seen level of authority over how music is distributed, discovered, and paid/not-paid for. Its ultimate goal is seemingly to build brand loyalty in the “magic” of Spotify, to embolden that authority. Playlists are the top tool they are currently employing to expand their platform empire. To interrogate the world of playlists is to interrogate the world of Spotify and its unprecedented grab for power and control in music.

If you open Spotify right now, the first thing you’ll see is “Browse”. The Browse page, launched in 2013, is how Spotify channels mood and genre playlists, algorithmically created “discover” suggestions, a curated feed of New Releases, charts, and a concert feed based on listening. At the top of the page, you might see New Music Friday, #ThrowbackThursday, Good Vibes, or Acoustic Summer. Chances are you’ve seen Today’s Top Hits, Rap Caviar, or Rock This, three of the platform’s most popular. There is a different Browse page in every country where Spotify exists.

“Spotify basically owns all of the visual real estate and the playlists,” explains a digital marketing staffer from one of the major labels, who wishes to remain anonymous. Let’s call him Jeff. “That’s all the Spotify staff curating that, and they’re investing weekly marketing updates from labels and distributors saying, ‘Hey, there’s a new Lorde song coming in three weeks.’ They sort this information and decide what gets placed on the New Releases home page, and what tracks get put into different playlists.”

Browse was partially created by employees of Tunigo, a music recommendation app acquired by Spotify in May 2013, and followed the introduction of Discover and Stations. When Browse launched, the idea was to help users discover playlists created by Spotify staff as well as the best user-created playlists. But over time the latter priority has taken a backseat in favor of boosting Spotify brand loyalty.

“A few years ago, it was more of a wild west in the playlist world,” says Jeff, explaining that companies like Filtr, Digster, Topsify could exist and gain traction, as well as individuals who could create playlists that users could find through Search. “If I wanted to find a psych rock band, I could say, ‘Okay, Joe in California actually was one of the first people to make this playlist and it has 50,000 followers’. There was a function - and labels were doing this - where you could message people within the client. I did this with my band. I would find someone with an Indie Morning playlist that had 5,000 followers and send them a message saying, ‘Hey, check out our song, put it on your playlist if you want.’ And a few people did.”

Jeff puts Filtr, Digster and Topsify in the same camp as average Joe in California, but of course that’s not the whole truth. These are huge companies. And the major label influence within Spotify is unsurprisingly vast. The majority of the so-called “editorial” content is shaped by Spotify’s relationships with the major labels and if not directly, then indirectly, a way in which they uphold the marketing agreements within their deals.

“When Spotify launched, the major labels had to sign deals to license their content,” Jeff says. “Part of that was that the labels have access to gratis advertising inventory. So if you’re a non-paying Spotify user, and you get an ad for McDonalds, and then you get an ad for Ed Sheeran, the Ed Sheeran one is coming through Atlantic and Warner Music Group. Because they have that inventory every month. The majors also bought Topsify, Digster and Filtr. These were independent companies that were early on Spotify." They already had large followings, hundreds of thousands of followers, and thousands of playlists.

Outside of the Spotify staff-curated playlists, those curated by Filtr, Digster and Topsify have more visibility on the Browse pages than any other playlisting brands, individuals or labels. With these playlists, employees of Filtr, Digster and Topsify can simply log in and add tracks. “Things like Topsify, Digster and Filtr remain good resources, especially for [major label] developing artists,” says Jeff. “I know that I plug in such-and-such track to five [of our] playlists and start to rack up some plays, some revenue for that artist, get it in front of some new listeners, and you also get some algorithmic stuff going. Like Release Radar and Discover Weekly.” By using Filtr, Topsify and Digster playlists to generate activity on their own material, the majors effectively use these playlists to pump their artists into Spotify-owned algorithmic playlists.

Often on Spotify, even paid subscribers will see front-page advertising takeovers promoting major-label playlisting brands disguised as “announcements” rather than “advertisements”.

“All of the major labels get an allocation of Home Page Takeovers that we pay for,” says a major label playlist brand employee who wishes to not be named. Let’s call her Carrie. “They decide between the curation, sales, and marketing teams what playlist or collection of playlists they’re going to promote that day. We’ve got some quite intelligent backend add systems, so we can actually change what you see depending on what time of day you log in. Mobile Overlay is also really important for us particularly within Spotify.” Carrie curates roughly 30-40 playlists spanning decades, moods, activities, and genres, working globally on Spotify, Deezer, Apple and Youtube. She also is part of her label’s international marketing team.

Carrie, whose background is in radio, calls making a playlist a “brand building exercise”, thinking of all the components that make up a playlist’s brand: the artwork, title, description, first block of songs. “Whether you’re listening to Today’s Top Hits or Pop Rising or Rocked, if you’re not going to go back and get the best experience for that mood or genre, regardless of who the owner is, [users] will see through that,” she says. Carrie's job, of course, is balancing her playlist brand building visions with her label’s business needs.

While some major-label entities have their own Spotify playlist identities, like Sony Music Classical or Sony Music Gospel, the playlist brands (Filtr, Digster, Topsify) seem intentionally disguised. “[It’s] almost like a Procter and Gamble,” says Carrie. “Procter and Gamble own all of these major brands, like Pampers and stuff like that, but no one really knows who Procter and Gamble are. That’s the ambition. [We are] the parent brand, but it’s not the main one that we’re pushing out there, or the one that we want all of our users to connect with. It’s just kind of the name for it.”

There are challenges for any labels and artists of all sizes when navigating Spotify, says Carrie. For example, Spotify controls what their cover images look like. “We are restricted within Spotify for certain rules and guidelines,” she says. “We can’t put font in certain places, we can’t use certain color schemes that are too similar to Spotify’s. There’s a whole guideline that helps steer where we have to go picture-wise.” Carrie explains a recurring “Browse pitching process” where playlist brands will pitch their playlists to Spotify, who decides what ends up in Browse. “You try to present it in the best light, like how many followers, how many streams. What is the history like? Is the graph of growth going steadily up or did it actually peak this time last year? Have the audience lost interest in the name of the playlist or the style of music, or perhaps are you as a company not putting enough effort into it? They will analyze it. But they are currently not open for any pitches for Browse submissions. I don’t know if that’s going to happen in the foreseeable future, but I imagine they will because it hasn’t been updated for some time.”

When tracks have a higher number of playlist placements, the song’s general ranking and chances of appearing on Spotify’s algorithmic playlists will increase. The position of the song on its playlists (whether it appears in position one, or position two, or position 27) also boosts its odds at getting on algorithmically made ones, Carrie says.

Majors can put money into their Filtr, Digster or Topsify playlists through paying for marketing. “With any playlist you need to build that brand over a longer term or with off-client placement (such as a magazine or via being a personality) or pay to feature in HPTOs [home page takeovers] or other to build awareness,” says Carrie. “Especially if your playlist isn’t in Browse, people can’t find it very easily.”

In situations like the major label home page takeovers, the line between what is paid-for and what is editorial on Spotify is nearly impossible to parse.

For Spotify’s newly announced “sponsored songs” (which allows labels to pay for songs to be played onto popular playlists for free users), sponsored content is also not marked. And of course, this dynamic also surfaces beyond the placement of privately-owned playlist brands, front-page advertising space, and sponsored songs. Even when it comes to the “human curators” at Spotify who program Spotify-owned playlists, the editorial voice of Spotify is largely shaped by the interests of major labels. “It’s a total partnership,” Jeff says. “If Spotify supports an artist in a big way, that artist will maybe evangelize the platform on their social media. Then people who are still listening on Youtube, or buying singles, might use Spotify instead.”

If it were up to Spotify, this is largely how their playlists would be shaped. Spotify does not want things like Filtr, Digster and Topsify to exist on the platform so much as it wants everything on the platform to be Spotify branded, something that convinces users of the “magic” of Spotify.

Indeed, Spotify would like to be more influential than record labels. Spotify would like for playlists to be more influential than albums.

This is why, now, if you search for an artist’s name of Spotify, the “Search” feature will deliver you a Spotify-curated, saturated-cover playlist anthology of that artist’s work (for example “This is: Lorde”) and other playlists they’re on before it will show you their most popular album.

Pay-to-playlist is real. For labels to influence Spotify-created playlists, Jeff describes a whole network of back-scratching and gatekeeping. While money might not be directly changing hands between majors and Spotify for direct access to playlist, there is a bigger picture where labels and Spotify provide value for each other - things like driving social traffic by getting artists to post Spotify links, doing paid media, and advertising. “If you can go to these [streaming] accounts and say, we have a $5,000 ad plan, and we are going to drive exclusively to Spotify...” he explains. Well, isn’t that a relationship they will want to keep mutually beneficial?

Advertising plans on Spotify were long out of reach for most independent labels due to a previous requirement that labels spend at least $25,000. Only now as a result of a new deal struck with Spotify by the independent label group Merlin, a “multi-year global license agreement for the world’s leading independent record labels,” are some things beginning to change. (It’s worth noting that Spotify’s press release about the deal proudly calls Merlin “the virtual fourth major”.) At the A2IM conference in New York City in June, a presentation from Spotify’s independent label liaisons explained some of the ways going forward that indies might better access Spotify, including eliminating the $25k minimum for ad space. It also outlined potential playlist strategies, but there was no mention of representation for indie-curated playlists on Browse.

At the major label where Jeff works, there are four or five people whose job is solely Spotify relations. At Spotify, there are one of two people who just work with his label. The process for major labels to get their songs on playlists is not unlike how they service radio. “It’s a pitch, usually marketing points in an email or in an Excel grid,” Jeff says. “For higher level artists there might be a dedicated phone call about that artist. Or an in-person meeting, introduce them to the staff. They want to know why somebody would be listening to this song. Why they should care about it. Is there a sweet press campaign? Is there radio? Is the artist touring? Do they have any brand deals?”

For all of its talk about prioritizing “discovery” and “knowing your tastes” ("I just want to meet a girl who knows and loves me like my Spotify Discover Weekly playlist," read a Spotify ad last year), what Spotify feeds to Browse and pushes to Discover is influenced largely by whether an artist already has a massive marketing campaign and corporate push behind them.

On the day that Jeff and I meet up to discuss the world of playlists, Ed Sheeran has just dropped his new record. We go to Browse, he’s that day’s Premium homepage takeover. He’s on the cover of New Music Friday. There’s a featured This Is Ed Sheeran playlist. On “TGIF” he’s got the top track. “New Releases”, top track. In Pop, he’s on the cover of Today’s Top Hits. “I imagine they started this conversation six months ago and have just been talking about it continuously,” Jeff tells me, explaining that the label would outline the whole album roll out plan. “And then I’m sure Spotify put together a dek, or a presentation.’” There will be a constant stream of communication through the campaign. “They’ll follow up and be like, this song is performing really well so we moved it up in a playlist.”

As Jeff explains, any artist can “deliver their content” to Spotify through a service like Tunecore or CD Baby, but that does not mean all artists have access to being visible to users. This requires the same level of professional, paid-for services that has always been the work of PR and radio promotion companies. For some artists, especially independent artists, this path of communication and access simply does not exist.

“It’s really that next level of communication where there’s weekly calls, there’s just constant contact. They have weekly calls. There is a process of sending a priority grid every week that’s like, for the distributors, here’s our 80 titles that are coming this week. And in the case of Warner, a company that distributes indie labels, you can have artists [independent labels distributed by ADA] on the same grid as Ed Sheeran or Green Day. And that’s all coming in an Excel sheet or something over to the Spotify reps. Then they take it, and they’re like, ‘Okay, what’s coming this week? Do we like it? How do we wanna support it?’ These people have a lot of authority.”

“Sometimes Spotify will say, okay cool, and start them on a lower or mid-tier playlist and see how it performs,” says Jeff. When he refers to “mid tiers” he is getting at the hierarchy of playlists. “Rap Caviar is the ultimate hip-hop playlist,” he explains. “I was working with an artist who had run up 20 million plays on Soundcloud with no promotion. It was one of those viral hip-hop things. So they were like, ‘Okay, we’ll put him on a playlist called Most Necessary’ which is like a feeder playlist. They’ll see how the song performs. They’ll look at stuff like skip rate on a song. Like, oh if someone listens for 15 seconds and then skip, that means the song isn’t really reacting. But if it has a high completion rate, or a low skip rate, then maybe they’ll test it in Rap Caviar and see if people like it.”

Playlist culture is introducing an unprecedented dependence on data. We hear about the stacked human playlisting teams, with “genre leads” and “junior and senior curators” building thousands and thousands of playlists. (Though we never see their faces or names on the platforms—Spotify’s way of building trust in the mystified Oz-like “magic” of Spotify, rather than human intelligence needed to program playlists.) These human curators are responding to data to such an extent that they’re practically just facilitating the machine process. As BuzzFeed reported last year, Spotify uses a performance tracking application titled PUMA, or Playlist Usage Monitoring and Analysis, which “breaks down each song on a playlist by things like number of plays, number of skips, and number of saves.” PUMA also tracks “the overall performance of the playlist as a whole, with colorful charts and graphs illustrating listeners’ age range, gender, geographical region, time of day, subscription tier, and more.” In the “human curated” playlist factories, human beings essentially reproduce the work of the algorithm.

At the major label playlisting brands, they have these sorts of tools too. “We have this fantastic backend tool which allows us to analyze playlist performance regardless of the rep owner, but also look individually at track performance, obviously looking slightly more in-depth for [our own label's] music than others,” Carrie says. “It helps me to navigate specifically the Spotify environment a lot more proficiently than I otherwise would be able to. So we can see our top performing playlists are both globally and per market.”

This creates a culture where artists are expected to climb the playlist ladder and hope the data stacks up. Jeff excitedly talks about his own band’s song recently being added to a Spotify-curated garage rock playlist that’s prominently placed on the Rock Browse page. “[It’s] a lower-mid indie rock playlist, but it has like 70,000 followers. That track is about to be our most streamed track. They refresh the playlist every few weeks and it keeps staying on there which is amazing. We’ve gotten a few more followers. Nothing dramatic. But when it hits people’s Discover Weeklies? If I look at that track, where our streams are coming from, it’s that playlist but it’s almost equally Discover Weekly.... A truly independent artist is probably not going to get thrown on Rap Caviar, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have an opportunity to be put on something lower.”

In response to how inaccessible these playlist curators can be, a whole industry has popped up around promoting to them. By many orbiting the industry, this complex of pitching companies is commonly referred to as a “new cottage industry”. The business meets somewhere at the crossroads of public relations and payola—a tradition as old as the music industry itself, historically used to define the illegal practice of record companies paying for commercial radio airtime. (Under U.S. law and FCC regulations, Payola is illegal on radio, but those laws do not apply to digital streaming platforms.) According to a 2015 Billboard article, a major-label marketing executive confirmed that pay-for-play is (or was) definitely happening.“According to a source, the price can range from $2,000 for a playlist with tens of thousands of fans to $10,000 for the more well-followed playlists.” And many are already calling the platform’s new “Sponsored Songs” endeavor a 2017 incarnation of payola.

Spotify pitching companies like “Playlist Pump” have also popped up, claiming to assist independent artists with doing “what only major record labels were able to do in the past - offer massive exposure for artists through direct relationships with curators of many of the major playlists featured on Spotify”.

An unspoken component of playlist culture is that playlists exist largely to make music more easily commodifiable. Spotify's "Sponsored Playlists" program makes it easier for them to sell advertising spots to corporations. “With Sponsored Playlist, it’s all about matching the playlist to your marketing goals,” Spotify writes on its website. “Cardio or Power Workout are perfect for a footwear brand expanding from lifestyle shoes to workout sneakers. A QSR adding breakfast to the menu? How about Morning Commute? An entertainment company with a summer blockbuster teeny-bopper flick? Teen Party, of course. You get the idea.”

“It’s all about the playlist,” explains Spotify in their “Spotify for Brands” marketing video. “Our playlists are key anchors of the Spotify brand and experience.”

It seems commonly understood that for major-label owned playlists, their days on Browse are probably numbered, as Spotify seeks to tighten its control over its own platform and product. But looking into their history provides a look into the foundation of Spotify’s past, present and future, and the politics of playlists and marketing on Spotify. Spotify might change who has access to its playlists and ‘Browse page’ by nixing these third-party visibility and giving an inch more space to independents, but it's business interest will always be its own brand’s power and growth.

The tech industry likes to highlight the positive impacts of innovation on culture and society, while ignoring the negative. Uber will pride itself on flexibility for drivers without owning up to how it fucks over workers. Facebook will promote its facilitation of a community without talking about the data it mines and sells or its lack of social responsibility with regard to how news is spread. Similarly, the music and tech industries have yet to really acknowledge the ways in which Spotify and playlist culture are unapologetically harming independent music: the pro-rata business model that favors no one but pop stars, yes, but also the ways in which playlisting waters down human relationship with music through cold and automated ways of programming, all in order to corporatize art and literally, literally, make music fit into Spotify (and Apple, and Deezer, and Google Play)’s tiny, square tinted boxes. Instead of pushing back on this reductive way of thinking, instead, thus far we have seen only a flurry of puff pieces about playlist curators as “secret hitmakers” and features praising them as “unsung heros”.

The commodification of social interaction is massive dilemma of our time. And one of the main ways in which music fits into that conundrum is emerging with playlists—the commodification of swapping mixtapes, long a cornerstone of music culture, possibly the most personal and emotionally resonant way to share songs. The rise of data-driven playlists marks a frightening marriage of human and machine thinking in how music is programmed, a way of thinking once reserved for commercial radio and now pervasive through all levels of the industry.

Talking to friends who are independent musicians, I have heard all sorts of stories, from labels encouraging them to make the first track on their record one that could be attractive to those who find it through Spotify, to artists being congratulated over being added to mood-based “feeder playlists” that are “huge deal”. When major labels and independent labels alike reify this machinelike way of thinking, is it harmful for creativity and imagination? As human curators reproduce the work of the algorithm, what direction does music head into? Perhaps the secrets are hidden in plain sight.

By Liz Pelly, distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.